Following up on my previous post, The Bill Evans Question, I will discuss the aspects of Bill’s playing that raises him above nearly all of his contemporaries. I will also discuss some of the criticisms leveled against him.

Following up on my previous post, The Bill Evans Question, I will discuss the aspects of Bill’s playing that raises him above nearly all of his contemporaries. I will also discuss some of the criticisms leveled against him.

Specifically what I feel makes him great are the following:

*influence

*personality/identity

*continuity of conception

*motivic mastery

*harmony/inner voice mastery

*pianistic control

*song arrangement conception

*ballad conception

*compositional approach

*ideational permanance

*rhythmic conception

Here are the criticisms against leveled against Evans. Some of them I agree with. Some I don’t:

*Doesn’t swing

*Can’t play the blues

*Rushes

*Time feel issues

*Questionable repertoire

*Lacking spontaneity

This will be a lot to bite off in one sitting so this will be presented in several parts. Let take each area in depth.

Influence

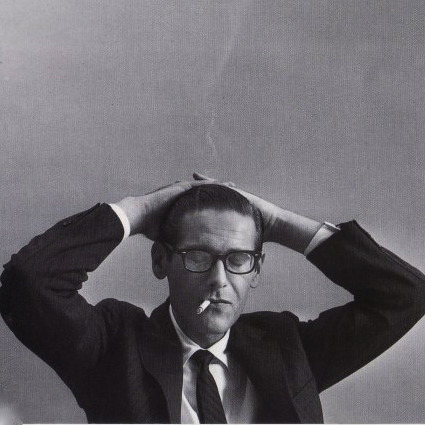

As mentioned in the previous post, The Bill Evans Question, the most objective yardstick for artistic contribution is influence on other players. His documented influence on 3 major pianists of our era, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Michel Petrucciani should be enough to dispel any hyperbolic claims to the contrary. Keith Jarrett is often quoted as being influenced but I have never heard him mention it so I leave him out. But other noted jazz pianists for sure would include Richie Beirach, Fred Hirsch, Lyle Mays, Eliane Elias, Bill Charlap, Alan Pasqua, Steve Kuhn, Chucho Valdez, Marion McPartland, Kenny Drew, Jr, George Duke, David Benoit, David Hazeltine, Enrico Pieranunzi, Andy Laverne, Danny Zeitlin and Warren Bernhardt. There are probably countless others, however these are ones I can verify for sure. Much of Bill Evans influence could be best summed up through his own words, that many people can realize styles through his approach. Quoted from the noted NPR Restrospective (narrated by Nancy Wilson):

“I could see where I could be an influence because I think what I’ve done is I’ve put something together which is not eccentric and it’s something that somebody could pass through also; they could become influenced by it and its not so highly stylized- I think. At least that’s the way I see it.”

This kind of humility is rare. One more thing to love about Bill.

Generally speaking Bill Evans laid the strongest foundation for the contemporary style of piano we are using today. If not him, who else in the 50s could you attribute it to? Ahmad Jamal to a degree. But this really was the line to Red Garland and Hampton Hawes and Carl Perkins which also intermingled with Oscar Peterson and Phineas Newborn. It was just an entirely different sound and style emphasizing the hard-swinging approach. As soon as Bill exposed his musical approach with his unique partner, Miles Davis, everything changed. The moody, sophisticated harmonic style of piano was now announced. Where he sat in the continuum and the innovations he introduced specifically when he introduced them (~1957-1961) is very important. He was a very specific voice that was different than his contemporaries who were moving much more slowly on continued lines. Bill’s restraint and flexibility in not pushing 4/4 “tipping” style was just something he heard. He sometimes seemingly moved backwards against the beat and took many unexpected rhythmic turns. Maybe some preferred the straight-ahead style but this was another voice that had obvious impact on the direction of music out of the 50s and into the 60s.

Go to Next Evans’ Post: Bill Evans Explained – Part 2

Previous Evans’ Post: The Bill Evans Question

Discover more from The Raney Legacy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

7 Comments

Dave

Hi. Nice post. Could you give a quick explanation of what “tipping style” is?

Thanks.

Jon Raney

Tipping style (or tippin’ probably more commonly) is probably the jazz equivalent of the word kids use these days, “slamming”. That said in hindsight the choices of words could’ve been better, because tippin’ implies a value judgement about positive feeling as much as locked to the groove. There is definitely positive feeling there.

My overall point to make is that, when you think of players like Oscar Peterson, Red Garland et al, it is more about sculpting a line within a particular eighth note line pocket that gives the impulse to tap. It’s more about the rhythm in a way than the line. That is not to say that groove isn’t the major thing or OP and RG don’t play great lines, they do. It’s a sense of the orientation. And I think there is room in there. The “don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got” police will be all over that. To a degree, Bill’s playing defied the conventional pocket with the way he played his particular brand of post bebop. The way he integrated little filigree runs and used triplets was his way of doing something just a little different and unexpected. Remember Parker was accused of “not swinging” from the “swing guys” perspective.

As examples listen to his work with Miles on “Love for Sale” ’58 Miles or his own “Peri’s Scope” from Portrait in Jazz. It’s not an issue of anti-groove playing is an issue of widening the scope a little to the tap your foot variety emphasized by Peterson and company. For example a lot of Peterson’s playing can get mechanical when he is uninspired. Sure he’s hitting the groove but he sometimes just sounds like he’s following his fingers. This is an odd contradiction for someone I consider a master pianist but one of struggled with and others too.

Steve

I’m glad I’m not alone in thinking there was something wrong with Bill’s playing towards the end.

My brother and I saw him at the VV some months before he passed, and we agreed that BE was doing something different that just didn’t seem to work as well as his previous playing.

To illustrate the magic of BE’s touch on the piano, my brother, who isn’t a musician, is able to recognize that BE is playing, even when I play him a bunch of other pianists; within a few measures!

Sure, there are some BE recordings that I don’t like, but that’s true with all players- no exceptions; especially with players who were over-recorded like Bill and Oscar.

Phineas Newborn and Ahmad Jamal seem to be the most consistent players IMHO, but that’s just because they didn’t record as much as BE or OP.

Sure, Bill didn’t swing as hard as some of the others mentioned, but he still swung all the time, however subtly.

It seems insane to have to feel that we have to defend an artist as profound as BE, but

the jazz scene today is getting so anti-jazz, nothing surprises me…

Jon Raney

You’re always doing this to me Steve:). This Bill Evans post is part of a series. this very subject, personality/identity and being able to recognize within a few measures is the focal point of part 2 which is due to be published in the next few days.

Steve

I just saw your great post on Organissimo. The reaction was split between the people who know the truth, and the Down Beast readers.

I’ve had it out with the DB readers, and they’ll never change their minds; after all, “it says here in my Down Beast magazine…; – )

Jon Raney

I stirred it up some more and my more critical comments will probably be good for at least 20

threads and counterarguments but I’m done:)

I thought I swore off this shit?

lol

Steve

LOL!! You thought that NG was bad; you wouldn’t believe some of the stuff that goes down there!

They got very upset when I said Kenny Burrell couldn’t play on fast tempos as well as your Dad, and that he didn’t play the head to Stolen Moments with Oliver Nelson’s harmony. It went on for over 100 posts!; – )