At times, I get inspired to talk about two particular aspects of Jimmy Raney’s language often missed: rhythmic subtlety absorbed uniquely from Bird’s model, and the difference between “lick playing” and “non-lick playing”. I’ve blogged about it some but perhaps not enough.

Part of the reason I don’t do talk about it more is that it’s a mental slog both for the reader and myself – an investment on both sides. It also might come across as overanalytical of that which, on it’s own terms, imparts the complexity directly without “libretto” so to speak.

Nevertheless, not to talk about it, if the various forms of public commentary is at all a reliable yardstick, begs the question, are people just missing this?

There are two mediums that coax me into an extended musing on the topic, public groups & forums and YouTube videos.

In the case of groups/forum discussions I do post occasionally, but it feels a little overbearing and perhaps a trifle overindulgent for me to chime in with lengthy expositions on the subject, so I try not to overdo it.

With YouTube there are 2 varieties of Raney appreciation videos (Doug too recently) , self-posting of transcriptions and “Jimmy Raney’s best lick videos”. The former I mind less given it’s indirect nature is to praise but I can’t help but think of Stuart from Mad TV…

Ok, I’m being mean.

But anyway, in terms of Jimmy Raney how to/best lick videos I get more annoyed because it goes beyond dedication to a point of “in-the-know” pretense; it’s just cheapening the achievement and borders on disinformation rather than information.

Sure he plays this particular link on this II-V but the more pressing question is, why does he play that there or why on that beat as opposed to another? There is also the larger context of the extracted lick that is seemingly ignored: What was his overall compositional process that pointed to and lead up to that “lick”?

Which then leads to the next point worth making.

Raney and Parker were not lick players. Yes they repeated their stock phrases but they were living bits of language that got manipulated in different ways based on musical inspiration, informed intuition and context. This is what’s behind the inspiration to transcribe more solos from the same artist. It’s not the licks but the artists’ thinking process behind the phrase that you are trying to tap into.

So here’s an area that really tends to weed out lick playing from non-lick playing: polymeter. Firstly, why polymeter and not polyrhythm? I would say they occupy the same landscape but, For analysis purposes, polyrhythm refers to a specific scale, arpeggio or phrase nugget repeated intentionally in rhythm; polymeter refers to phrasing, grouping, and/or accenting notes across the barline, implying a larger metric space. (this is my own definition, btw)

Details aside, why would polymeter flesh this aspect of Raney & Bird? On the simplest level it refers to a compositional process that can’t be faked. It is by nature on a higher level of musical thinking – that is at once both consistent but subject to variability. If you’re thinking in larger sections of the music you are creating dissonances and resolution over a larger musical context and the process is largely intuitional . This is not lick-playing. It is meta-musical in nature

(and no I’m not constipated)

(Ha... as my mother used to say)

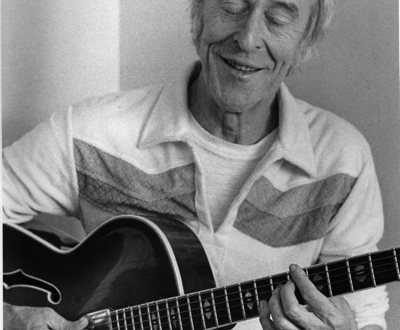

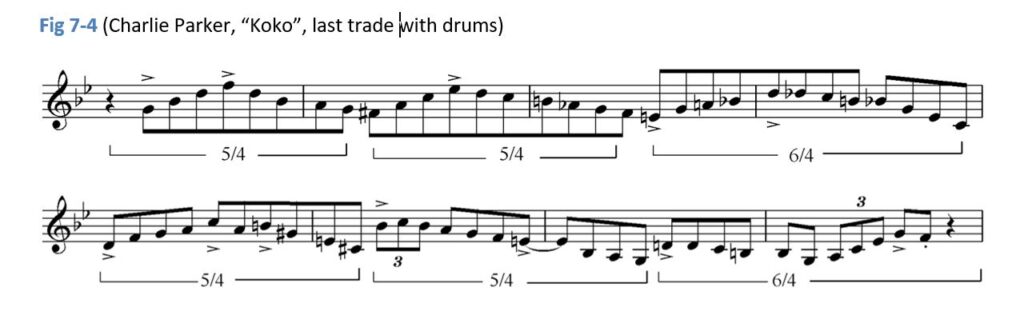

Let us get to some specifics here. There is one solo of Bird’s that Dad described as pivotal for him and reflects the polymetric nature of Bird’s playing: the out-chorus of Koko. Dad used to croak-scat it the best he could but here’s the actual recording of that snippet:

In my unfinished book about Dad I subjected it a a specific musical analysis:

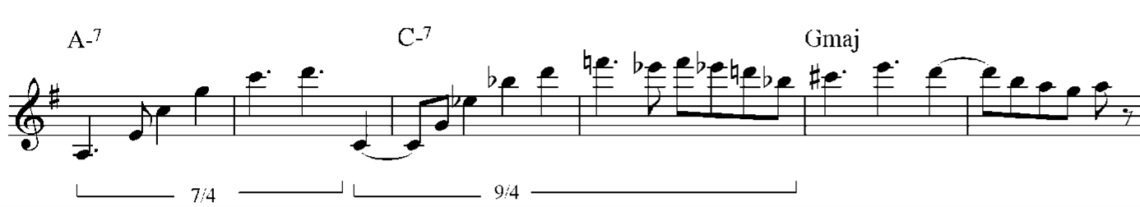

To explain it, I rearranged the solo according to its strong phrase lengths taking into account direction, arpeggio implications and accents. My interpretation of the solo’s phrase polymetric grouping is 5+5+6 x2 =16. This is a polymetric regrouping of the 8 measure musical space.

There are some who may regard this as speculative. I would venture that if you learned how to play this section, you would key in on the important 1st harmonic segments (the G-7, F#o, G7b9) how it resolves to the 3rd of C7 and falls into the very rhythms I described. Likewise the strong D-7 C#-7 phrase that implies 5/4 beginning in bar 5.

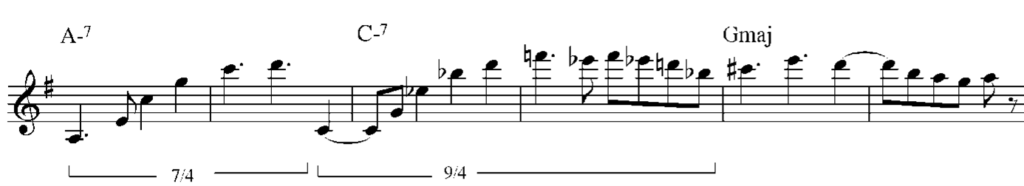

Here’s a comparative example of Jimmy’s polymeter on “Stella by Starlight” (in G) but slightly less complex:

Stylistically and intervallically speaking this snippet owes as much to Bach’s Cello Suite influence as Parker.

(Some of you may know that he also learned to play cello and ran through some of those Suites)

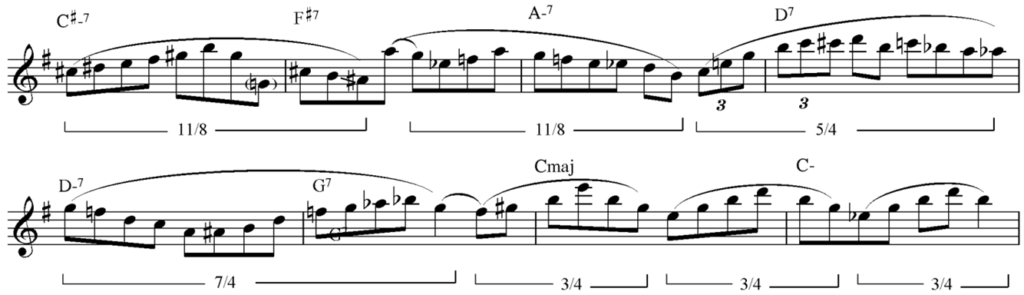

And here is an example from the same Stella solo where he phrased at the same level of complexity as Parker.

Again you might find the rhythmic analysis speculative but you would have to agree this reflects an extremely subtle and high level of rhythmic structure and organization. He clearly goes out in the deep and comes right back in where he needs to: on the 5th of tonic on the downbeat of G (next bar)

Either way, Submitted for your Approval

Discover more from The Raney Legacy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.