If you’re an English stickler over the use of the word evolve in its typical context – over a long period of time – then perhaps not. However, if you’re a musician of Jimmy Raney’s caliber, that weaves profound musical stories within just a few choruses with such precise yet inexorable logic, then Yes, it’s really a thing.

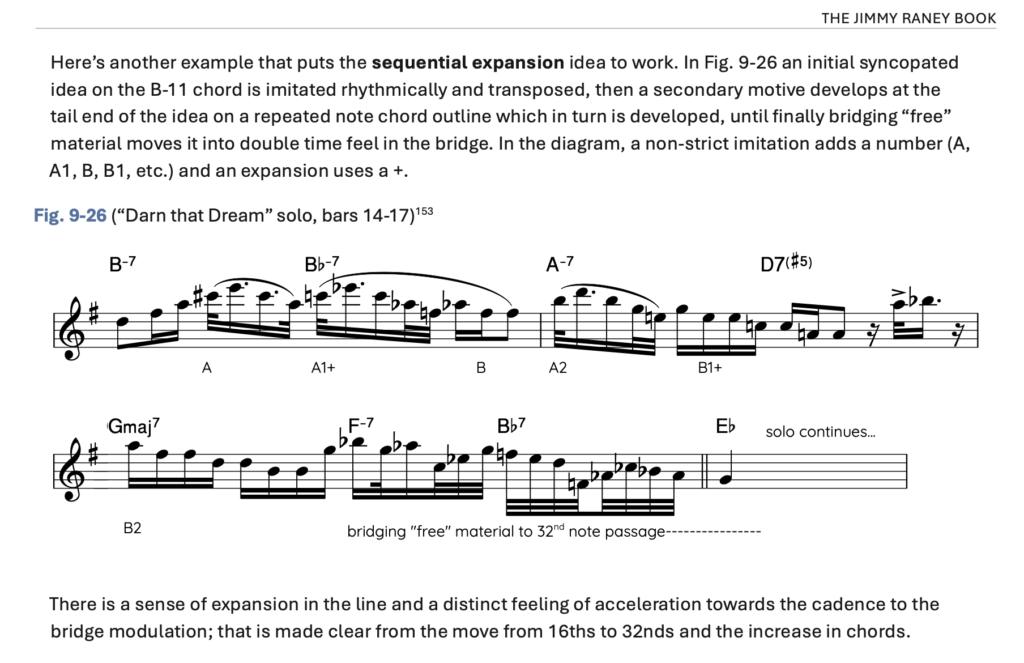

My coinage of this term took place in the 9th chapter in the section, “Evolving Sequence & Expansion” of the recently released, The Jimmy Raney Book. To a degree, describing how and what makes Jimmy Raney play the way he does in words is a bit of tall order, but I gave it a yeoman’s effort. To quote myself I offered this:

“Many have commented there is inevitability in Jimmy’s lines; they always seem to end up where there are supposed to. Part of that is his mastery of sequence in his lines but not obvious sequence schemes, as commented in earlier chapters, given that would probably lead to more commonplace results.

There is almost always commonality between phrases but with slight changes made, developing a portion of the previous phrase, and adding to it and then that piece itself is developed upon, until the entire larger phrase is built of these related, evolving pieces. Often the final piece is different from the initial but there is nevertheless a sense of having traveled logically.“

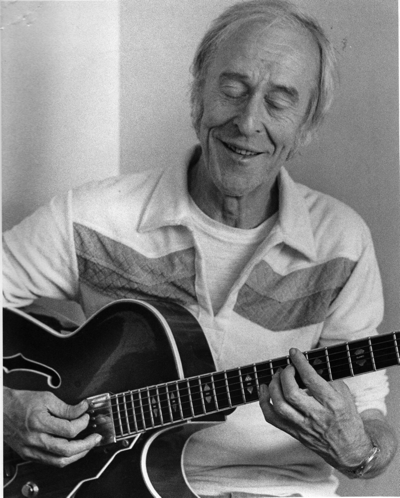

An incredible display of this type of cogency on the most difficult of all jazz forms, the ballad, is on full display on Dad’s version of “Darn that Dream” from Live in Tokyo. Below is a graphic showing the development scheme I gleaned from a passage of the solo just before the bridge, from The Jimmy Raney Book:

The concept of sequence, development and how rhythm and asymmetrical concepts play into Jimmy’s particular subtle brand of it, is frequently elaborated upon in the book. To describe this in the book I (might have) invented another term, “multi-measure syncopation” (sue me).

To further try to bring the examples to life I also created some YouTube Videos about them. The first video was about about displacement and asymmetrical grouping of measures featured in Chapters 2 and 6:

My second effort on YouTube was just released. The subject was over modified asymmetrical sequence. Again rhythm is a frequent subject throughout the book as it is a critical piece of Jimmy Raney’s style.

I think that on the subject of displacement (or what my father termed, “Harmonic Dislocation”) he is simply among the masters that are practitioners of this subtle dedication. Bill Evans for example said this in his interview with Marion McPartland on “Piano Jazz” on the subject:

“As far as the jazz playing goes, I think the rhythmic construction of the thing has evolved quite a bit. I don’t know how obvious that would be to the listener, but the displacement of phrases and the way phrases follow one another and their placement against the meter and so forth is something I’ve worked rather hard and it’s something I believe in, it has little to do with trends.

It has more to do with my feeling about my basic conception of jazz structure and jazz melodies and the way the rhythmic things follow one another and so I just try to get deeper into that and as the years go by, I seem to make some progress in that direction and do some things which please myself and I know its happening even if no one else does.”

Charlie Parker of course had a profound influence on Jimmy Raney, and is probably the one that contributed the most to this aspect of bebop and is what made his playing so compelling yet so vexing for those trying to learn it. The aspect that is so critical to understanding the genius of Charlie Parker is how the rhythmic and harmonic vocabulary was expanded under his influence and systematized.

I often cite a particular example to describe this – going into another room and listening to Parker and tuning out the rhythm section. You often might mistake an uptempo tune for ballad, where you thought he was playing 8th notes on a up-tempo burner when in fact he was playing 32nds or even 64ths on a slow number. We all know the stories of players turning the beat around listening to Parker’s displaced phrase as on the beat – that was sort of the point – to shoo the less able off the bandstand.

In terms of melodic phrase development and his philosophies, I find Dad also shares this kinship with Bill Evans. Bill Evans always plays things he means and he tries his utmost to follow-up with ideas that are just as related and meaningful. Without relying on flash or attempts to impress. The integrity of what he plays and what he chooses to play in reaction to a prior idea, is a commitment to melody and solo structure that is pretty rare, even among established professionals. That touch of magic that goes along with all that is also hard to reproduce and a shared trait between Evans and Raney.

But this subject brings up an important question in terms of jazz education which to a degree I’m now a part of. The fundamental question is “Can Jazz Be Taught?”. As Evans put in the “Universal Mind of Bill Evans” he said basically that “we ultimately teach ourselves.” So on the subject of teaching jazz successfully, I would say it depends.

If you commit yourself to solving how to make the best jazz possible in all its most difficult aspects and listen and learn from those that share and practice those same goals, then yes I think It can be taught.

But if we all ultimately teach ourselves, then I suggest, sign a contract with yourself and stick to it:

No more BS in my jazz playing!

I think this will go a long way towards your evolution.

Discover more from The Raney Legacy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.