The End of the Fifties, the Beginning of the Sixties and Tough Times page 1 | page 2 | page 3 | page 4 | page 5 | page 6 | page 7 | page 8| page 9|

The decline of jazz recordings outside of the major artists had probably already begun by the late fifties. One of Dad’s worst faults (and perhaps this is a just a Raney trait) was not being able to promote himself. He disliked the whole thing. His attitude was typified by how he told it me, “They know where I am. If they want me, they’ll call me”. He had his pride and also, his integrity. He wouldn’t do just anything for money. But he did what he could to survive and take care of his family, increasingly taking jobs he didn’t care for. Mom would say, “Why don’t you get an agent, then?” Trying to squelch the idea, he replied “Ok. Why don’t you become my agent?” Well, of course, neither happened.

One has to imagine though, what an artist of his stature could’ve done if he had a little bit of salesmanship, promotion, or even a bit of luck. There is no reason, given his artistic achievements, why he shouldn’t have gained the status accorded to Jim Hall, Stan Getz or Bill Evans. He was highly respected, even revered. Still, Jimmy wasn’t getting the respect he deserved and not being given dates as a leader. He was on many records led by others, and whatever solo space he was given was easily the standout contribution on the record. He was in the prime of his life, and one of, if not the greatest, jazz guitarists alive and yet he was completely underestimated commercially and therefore made to struggle while trying to make ends meet.

Jimmy in the late 40s and early 50s was young and all about the music and drank very little. But with hanging out, access to liquor, heavy drinking friends, domesticity and a heavy dose of the realities of a life as a musician, things started deteriorating. The responsibilities of fatherhood weighed on him.

In the latter half of the 50’s, the inevitable happened, Jimmy became a heavy drinker. He adored Doug but probably found he was no longer sure of himself and found solace in drink. Jimmy tried Broadway shows, but didn’t really enjoy the experience much. In 1960 he did however manage to be a part of the Broadway show, A Thurber Carnival. James Thurber was one of Dad’s literary idols and he was quite happy to be a part of the production. To boot, the music was jazz, with a quartet led by composer and multi-instrumentalist Don Elliot. The group consisted of Eliot, Jimmy, bassist Jack Six and drummer Ronnie Bedord. Jimmy and Lee became good friends with members of the cast, in particular, Peggy Cass and John McGyver. The show, however, only lasted nine months. His stint at the Blue Angel also ended at this point. For musicians, when things are tough economically, it often seems like gigs disappear when they are supposed to be materializing. And more challenges were to come. The writer of these lines was to make his appearance in August of 1961.

But still at this point, we were living—by outward appearances—a happy life: husband and wife, two kids and a cat, in the nice neighborhood of Briarwood, Queens. Jimmy also did many quality studio dates among them in 1962 with Gary McFarland, Lalo Schifrin (play link below for snippet), Eddie Harris and Dave Pike. (As close as Jimmy came to making a record with a “Blue Note” style sound and rhythm section. click on the link to see my prior blog post). He also toured with Stan Getz again  . His playing was perhaps stronger than ever, featuring a more direct attack Samba Para Los Dos.

. His playing was perhaps stronger than ever, featuring a more direct attack Samba Para Los Dos.

We moved briefly to Forest Hills, but even back then, the neighborhood was way out of our price range. There was also a fair amount of familial strife and a bit of trauma. Our beloved cat Pooky was killed by the neighborhood dog. We moved back to Briarwood later that year. Teddy Kotick’s family lived across the way from us and the families became close. Doug and I attended the local schools P.S. 117 and 217. But Dad’s drinking was getting out of control. He could no longer hold down music jobs consistently and his guitar was stolen out of his trunk.

The jazz music situation was not helping either. The Beatles had conquered the world and Rock & Roll was the rage. Jazz music was also going down a more abstract path in the hands of Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp and others, perhaps helping push jazz further from the mainstream. Dad actually took to a “regular job” to make money. He worked as a clerk in the Manhattan record store, The Record Hunter.

The Last Hurrah

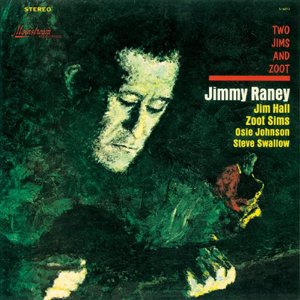

He did however have one last major ace up his sleeve before his long layoff and that was the brilliant record, Two Jims and Zoot on Mainstream Records in 1964. In addition to Jimmy, the record personnel was Zoot Sims on tenor, Jim Hall on guitar, Steve Swallow on bass and Osie Johnson on drums. During this point in time, bossa nova was the rage on the heals of Stan Getz’s “pop” breakthrough success on Jazz Samba and with Joao and Atrud Gilberto on the tunes “The Girl from Ipanema” and “Desafinado”. People would hold “bossa nova parties”; even jazz musicians with their discriminating tastes found the style both invigorating and intriguing – novel yet accomodating jazz sensibilities.

As I understand it, the intention was that this record to be, more or less, Jimmy’s bossa nova record and Stan Getz was to be on it. As it turned out, Zoot Sims did it and it is arguably some of his finest playing heard on record. The other twist is that the classic bossa nova selections (“A Primera Vez” “Presente de Natal”, “Morning of the Carnival”, “Este Seu Olhar” and “Coisa Mais Linda”) converted to swing feel and the one bossa on the record is Gerry Mulligan’s “Hold Me”. Jimmy’s playing on this record is some of his finest ever. His playing is forceful, his imagination is fertile and his chops are in abundance. But additionally, his sound and touch feels like it has evolved, the dynamics and the attack, in particular. There is, for lack of better words, a passionate elegance. When he executes a turn of phrase or leaps to finish an arpeggio, it can leave you breathless as he just seems to pull you in. He seems to have mastered the nuance and expressiveness of phrase that has really only been achieved by our finest horn players.

The record has some truly remarkable moments on it such as the guitar interplay moments between Raney and Hall exemplified by A Primera Vez. At this point in his career Jim Hall’s unique approach and artistry was fully established in jazz and was a perfect foil for Jimmy’s approach. What is revealed on these cuts in particular is Jim Hall’s ability to listen and compliment Jimmy’s poignant declarative lines with perfect and striking counter-lines. But this is not surprising given the similar sensibilities shown in his duo work with Bill Evans two years earlier on Undercurrent. In terms of Zoot Sims, the melodic beauty and sound and subtle rhythmic authority is astonishing. A high point for me is his gorgeous work on Jim Hall’s All Across the City. The arranging that Jimmy did for two guitars was perhaps his most subtle to date; intricate interlocking chord voicings and his penchant for counterpoint are in evidence. Steve Swallow and Osie Johnson provide a buoyant but strong time feel and coupled with the ambiance that the piano-less environment provides, perhaps set this record apart from prior records and gives it a modernity that is striking.

A humorous note about the date was told to me about Zoot Sims. Jim Hall’s quirky rhythmic tune, “Move It” had some difficulties with the chart. Jim had written out specific and fairly complex changes on it. As Zoot was struggling with it, finally my father told him, “Zoot, it’s just “Softly as the Morning Sunrise”. Zoot said, “Why didn’t you tell me?!” He then proceeded to tear it up as per usual.

page 1 | page 2 | page 3 | page 4 | page 5 | page 6 | page 7 | page 8| page 9|