*Note. The images items on this page utilize “collapse/expand” elements. The first two letter images are auto-expanded for your convenience. The remaining items require clicking the up or down chevrons (v ^) next to the titles to view the images.

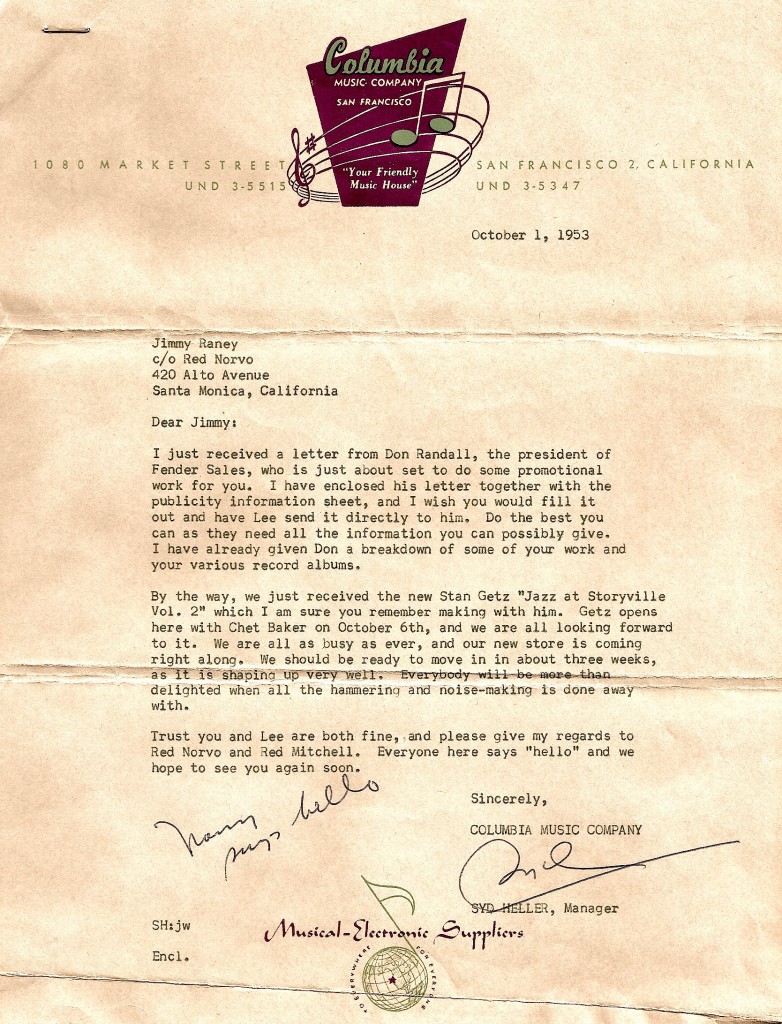

Don Randall, Fender Sales via Syd Heller to Jimmy Raney (1953)

This a chain of correspondence between Don Randall, the late President of Fender Sales and the marketing brains behind the famous Leo Fender guitars, Syd Heller, the owner of Columbia Music (no connection to Columbia Records) and Jimmy in 1953. At the time, Jimmy was touring with Red Norvo on the west coast and probably staying with Red in Santa Monica (see c/o). This probably came about because Jimmy visited Syd’s store in San Francisco. The store was sort of an all-in-one music establishment, carrying records, tapes, musical instruments, instruction books and had a small record production company on the side (perhaps a small recording studio as well though not sure). Syd was obviously a fan of jazz and Jimmy’s music and probably wanted to promote him with the help of Don.

Of note is the somewhat humorous section of Don’s letter, where he expresses his befuddlement about how anyone could not be using Fender guitars (Jimmy obviously was a devoted Gibson user) in particular the Telecaster which Oscar Moore was quoted as saying was “the best guitar he ever played”. Needless to say, to get Jimmy on the publicity bandwagon required a conversion to Fenderism from Gibsonism.

Obviously this never happened.

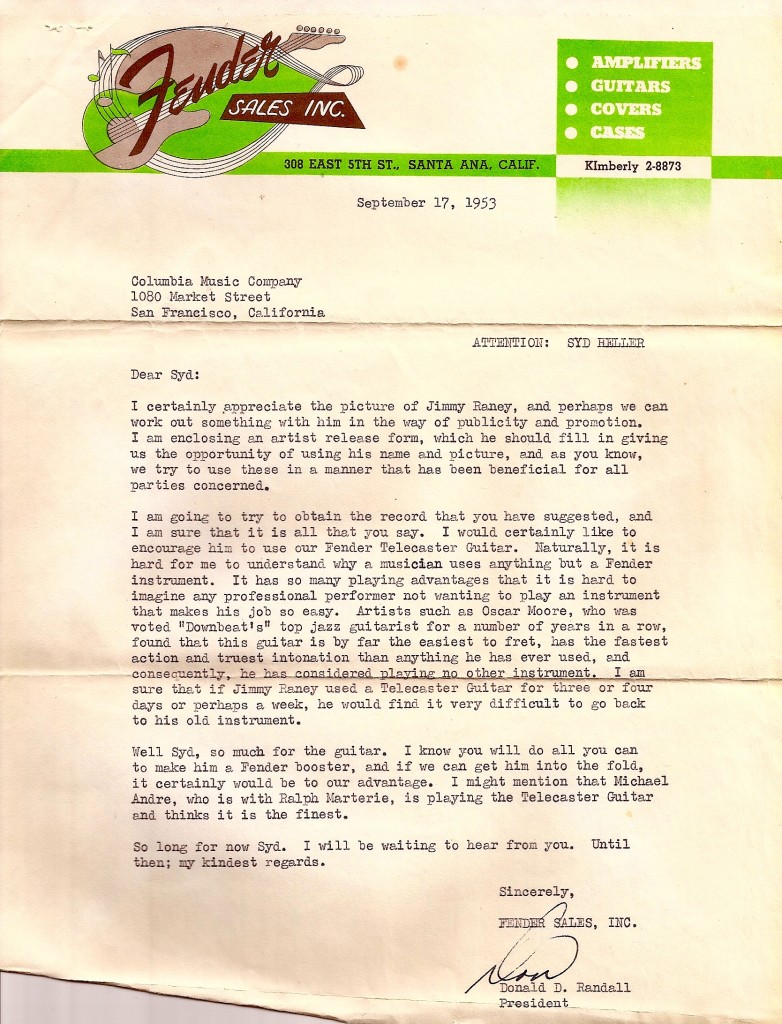

Letter from Jimmy Raney to Phil Bailey re: Birdland ’52 CD from John Scofield

This was a scan of a letter I received from Patty Bailey, the wife of the late Phil Bailey, jazz radio host in Louisville. My father was a guest on Phil’s radio show very often and the two were pretty close.

It’s a copy of letter from Dad to Phil on the subject of the bootleg album, Birdland Sessions 1952 Featuring Jimmy Raney – Stan Getz put out by Fresh Sounds records. He received the CD from noted jazz guitarist and Raney fan, John Scofield. An interesting note is that I remembered this story years ago but had thought that I my recollection was wrong and that I had invented a “fish story” about John and the CD. I had asked John myself if the story was true and he said he honestly didn’t remember.

A little while later, Patty looked me up and offered to send this correspondence – which by complete coincidence – completely confirmed my understanding of where the CD that I now have in possession originated from: John Scofield.

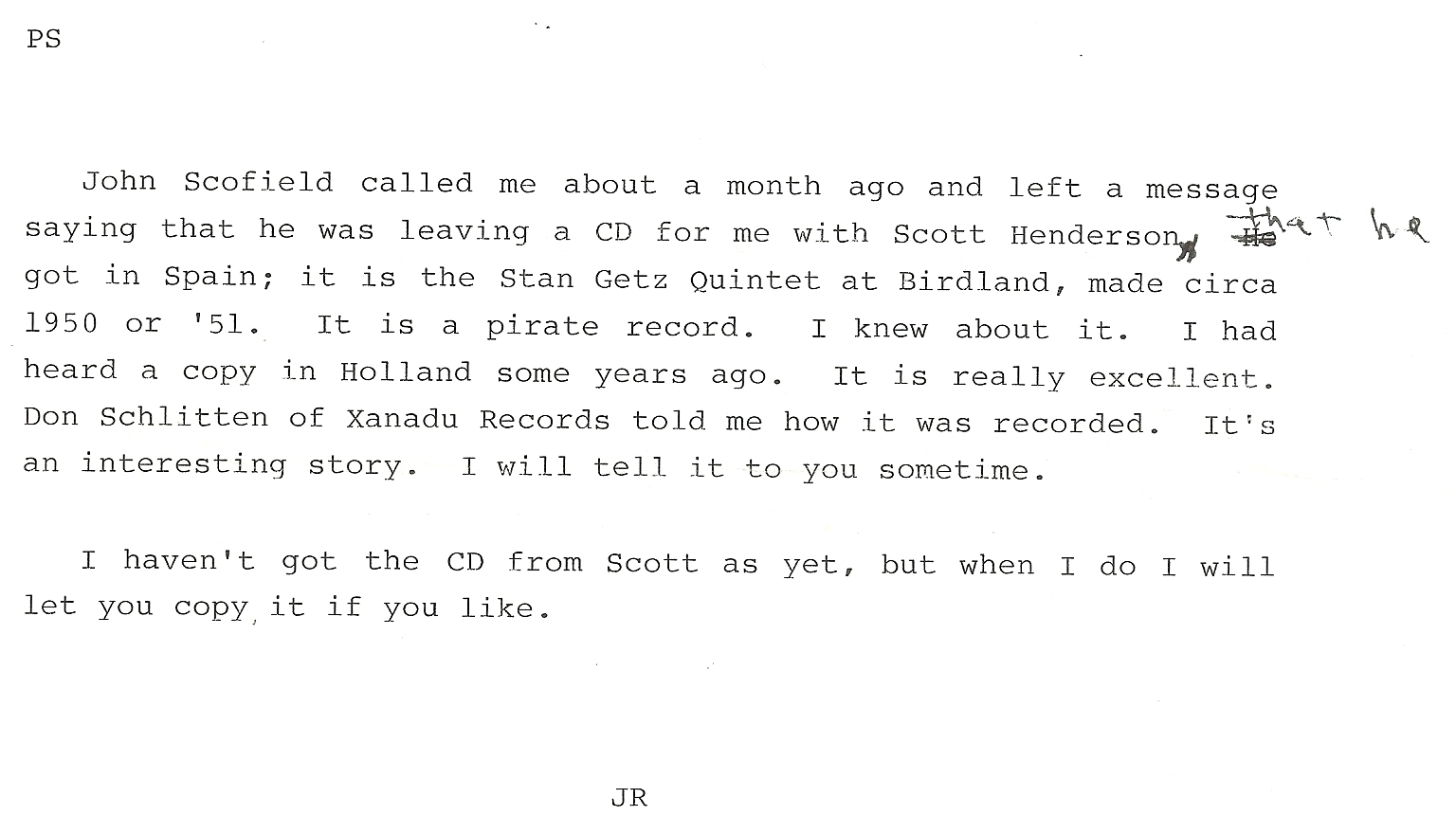

Jimmy Raney letter to Phil BaileyJimmy’s Humor Piece, “In Dixieland I’ll Take My Stand”

“How Did I Become a Living Legend”

“The Composer” (1990)

Vogue Music , “International Contract” for Jimmy Raney Visits Paris (1954)

We often romanticize about Europe (in particular France) having a greater appreciation for American jazz artists than in their home country, especially in the 50s and 60s. Although that may be true, when it comes to the business side of it, as you can see from the letter about Jimmy’s now famous Jimmy Raney Visits Paris, record company contractual legalise that screws over musicians seems to be a universal language.

And at least, spell his fucking name right…

Vogue MusicThings Downbeat Never Taught Me

Back in 1939 or 1940, when I was just starting out to be a jazz musician, I was a Downbeat and Metronome freak. I devoured these two magazines in search of news of my heroes. I’m not talking about Benny Goodman or Artie Shaw. They were household words to everybody, as the Gabor sisters, The Grateful Dead and Kentucky Fried Chicken are today. I’m talking about the guys who played jazz on offbeat labels. I knew they all lived in New York City, and had penthouses overlooking Central Park. I went to the movies and saw jazzmen (portrayed by Cary Grant and David Niven) doing just that. I figured maybe I could do that too, if I just kept practicing my hot licks. That’s what they called them back them–honest.

Louisville in those days was different than today. Back then there were only a half a dozen musicians who could play jazz, but couldn’t make a living at it. Nowadays there are at least ten times as many who can’t make a living at it. Louisville has come a long way.

Anyway, from reading Downbeat, I figured the only hope I had was to get to New York. I knew there weren’t any penthouses here, not to mention Cary Grant or David Niven. Since I didn’t have any money but did have and uncle and grandmother in Chicago, I thought I would try there first. It did have tall buildings, a lot of people, and Downbeat was published there, even if they only wrote about musicians in New York, they wrote it there.

Chicago turned out OK. There were a lot of talented young musicians, and they all played bebop. They didn’t get paid for it though. Nobody like bebop. Not the jazz fans, not the older musicians, not even the Downbeat writers. We mostly played for free in a B-Girl joint on South State Street called the “Say When”. They didn’t like bebop either, but they let us play there to make the place look like a real club, instead of a clip-joint that rolled drunks who were looking for some action. They got action all right, but not the kind they had hoped for. They ended up in the alley with a sore head and no money. The bartenders were all ex-prizefighters–they had to be.

I finally found a place where I got paid to play. It was called Elmers, and it was on State Street too, but not on South State Street, but right in the heart of the Loop. The leader of the trio was a man named Max Miller. His age placed him in the Dixieland-swing era, but his style was an unidentifiable creation of his own devising, and was more dissonant and modern sounding than either. He was a fierce looking man with a black walrus mustache, and a menacing, venomous grin. He was stocky and powerful and had a vile temper, and as a consequence everyone gave him a wide berth. He was an accomplished vibraphonist but preferred to play the piano, on which his technique was quite limited.

He had created a repertoire of originals and had quite a following. At least more than enough to fill his small club. The bandstand was located in the center of a semi-circular bar, and we hammered out his collection of peculiar pieces with such titles as: Heartbeat Blues, Blues for Beethoven, and many others whose names I have long since forgotten. For some reason he was quite fond of my embryonic bebop efforts, and treated me very nicely for a time. Our bassist was another young bebopper named Gary Miller, and Max really gave him a hard way to go for reasons I couldn’t fathom. Max would play some figure in his left hand and glare at Gary saying, “Dig this riff.” Gary, who had absolute pitch, would pick it up instantly. After a few bars Max, would shout at him, “Get off my road.” And so it went. No matter what Gary did, he couldn’t please him. It ended finally when a Downbeat writer came in to see us and asked Gary if he was any relation to Max. Gary, whose real last name was Malemud, said “He’s my father”, and the writer printed it. C’est finis pour Gary. A little while later it came to be my turn on the rack, and since I thought I played better than he did, I wasn’t having any–money or no–so we parted company.

There was another style going at the time in Chicago. This was the Lenny Tristano style. We beboppers didn’t think much of Lenny, and vice versa. As far as I could figure out, nobody liked Lenny’s music except Lee Konitz and his mother. (Lenny’s mother, not Lee’s.) He hated our music and we hated his, and everyone else hated all of us. Lee and Lenny left for New York City soon afterward, so we had the unpopular music scene all to ourselves.

After awhile, I got lucky. It seems that bebop was beginning to make some headway in New York, in spite of the critics, and some of our boys were working on 52nd Street. A couple of them had heard me in Chicago and recommended me for the guitar chair in Woody Herman’s new bebop band.

It was a great band, but there wasn’t much for me to do. I scratched around on my old rhythm guitar while my electric Charlie Christian model Gibson sat idly by. There weren’t many guitar solos for me to play. Finally Ralph Burns and Al Cohn took pity on me and wrote a few things. Anyway I knew my penthouse was still waiting if I could only get to New York to claim it.

After about eight to nine months on an old bus I was ready to cry uncle. They never told about this in the Glenn Miller movie “Orchestra Wives.” There were a lot of disillusioned orchestra wives with us too.

I stayed in New York after that. I figured I was ready to conquer the Apple and lay claim to my penthouse in Manhattan. We didn’t call it “The Big Apple” then. I think that was invented by mayor Koch and his P.R. men.

Things got better after that. I had made my first record with Stan Getz. I played it a lot. Looked at it a lot. Just think! I was one of those guys who had made a record for an offbeat label. Maybe there were kids out there wishing they were me. I made some more records with stars such as Buddy DeFranco and Terry Gibbs. I even worked jobs at Birdland with them. Still, all I had was a furnished room on 81st street and less money in the bank. By the time I got down to $60 I really started to get worried. I had started out with $2000 in 1948 dollars.

Artie Shaw came to my rescue by hiring me for what was to be his last big band. It was a fine band, as good as Woody’s and I got much more to play. I was afraid of him because I had heard how tough he was to work for, but it wasn’t true. If you could play he didn’t bother you. He seemed to care only about the music.

Unfortunately, the people didn’t care only about the music. In fact, they didn’t like what we were doing. They wanted to see the man who had married so many movie stars, and hear Begin the Beguine and Frenesi. He broke up the band and I was back in my furnished room with a somewhat smaller stash of 1949 dollars. I was getting a little better known around town by now. I worked maybe once a month instead of every three months. I was starting to get calls from people out of town and Europe wanting to find out which of the glamorous Manhattan jazz clubs I was appearing in nightly. My first telephone was my one tangible sign of success and adulthood, but I began to hate it. I started answering my phone by saying, “Grand Central Roach Control.”

I played and recorded with Stan Getz in 1959, ’51 and ’52. Then I did a one-and-a-half year stint with the Red Norvo trio.

After that I got married and settled down in New York City. I found out soon enough that you can’t make a living playing jazz in one city. Not even New York City, so I started doing other things in order to get by. TV jingles, club dates, recordings–both commercial and jazz-along with other stuff. I even did subs, and played the full run of two Broadway shows. That’s the nearest thing in music to stuffing mattresses for a living.

I met and played with several of the older musicians whom I had admired so much when I was starting out in Louisville. I met them while making TV jingles. Alas-they were in the same boat as I. I can’t complain though; I did make a living, and a pretty good one at that. I made a lot of jazz records over the years. Around fifty under my own name at last reckoning, and many more than that with other people, so I did OK after all. There were many who didn’t.

I never did get my penthouse, and I never met another jazz musician who had one either. I did visit a few now and then. They belonged to millionaire stockbrokers and the like. Perhaps it’s just as well I didn’t. I most likely would have fallen off the terrace when I was drunk.

See you in the funny papers–or maybe Downbeat.

J.R